Last week marked International Literacy Day, celebrating the many organisations and individuals across the world who play a role in helping children and young people to engage in the modern world and explore our rich histories, through literacy.

Last week’s post drew heavily from a book to look at existing ideas about questions in the classroom. This week, I want to set the scene of literacy accords the curriculum, and this link will take you to a good book that goes into far greater depth than I can in this short post: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Q3jsAgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=literacy+in.schools+cross+curricular&ots=1eQEa4Mvdq&sig=ofiSZOVpymvPu5LmFzccfCnxYKo#v=onepage&q=literacy%20in.schools%20cross%20curricular&f=false.

In particular the book gives a good introductory overview of how policy and practice has developed in relation to literacy in the classroom, including teacher training, national curriculum content and core literacy standards.

This week’s post has deliberately less of an academic thrust so examine that resource to your teaching needs in addition to this blog.

For some, the love of reading and the desire to write comes easily. For others the task is harder. Learning to read and write begins a long time before formal schooling. Vocabulary development, having access to a range of texts and understanding the goals of reading are all early building blocks of literacy later in life. In terms of building resilience in children who might experience all kinds of disadvantage (learning disabilities, family instability and poverty amongst other potential factors) that impact their ability to engage in education, literacy is a golden shining key of potential life change towards fostering aspiration and positive outcomes.

It is widely accepted that children have a range of different strengths and learning styles, being able to excel in Science or Music for example, whilst struggling to write legibly. In addition, those who are keen language enthusiasts (as I was at school) enjoy listening to and forming language, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that they will write or read to the same level (my own handwriting was compared in one report to a spider having fallen into the ink pot and then drunkenly crawling to safety across the page).

Perhaps for some children, experiences of literacy so far in life, whether at school or at home, or both, have been more difficult, perhaps they have not installed a feeling of mastery or success, and it is this feeling of accomplishment and progress, alongside the ability to see the purpose and benefit of literacy that fuels a desire to improve one’s skills.

I have two stand out memories of literacy in my schooling. One teacher made me read out my homework to the class because she felt it had ‘some sound merit’ in spite of the appalling handwriting. I found this embarrassing and uncomfortable. For a while, I avoided handwriting at all, and when I did I wrote in capitals so as to be clearer, until my RE teacher commented in red pen that I had ‘shouted my way through the essay’. Conversely, my English teacher at A-Level fuelled my love of both writing and reading, taking time to discuss my reflections on the novels we studied and engaging in a dialogue over the written work that went beyond handwriting to consider positioning the reader, forming an argument and poetic description. It was the first time I really considered literacy to be anything other than handwriting.

UNESCO recently released new data that shows that 115 million young people between the ages of 15 and 24, still cannot even read or write a simple sentence (http://www.uis.unesco.org/literacy/Documents/fs32-2015-literacy.pdf). This data indicates an urgent need for international communities to step up to the challenge of ensuring all children have access to education that places literacy at the heart of the curriculum. Whilst South and West Asia and Sub Saharan Africa are the geographical regions with the poorest literacy rates, in the UK, we are faced with a striking and unacceptable gap in attainment for vulnerable children (looked after children (http://www.literacytrust.org.uk/assets/0001/4326/Looked_after_children_and_literacy_LP_review_2012.pdf), children from low income families (http://www.savethechildren.org.uk/sites/default/files/docs/closing-the-achievement-gap.pdf), children with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties and children with physical disabilities).

In response to national concern about literacy levels, the term ‘literacy across the curriculum’ is now a well worn phrase used in most schools to describe the joint effort of all teachers within the school to transfer and apply the generic skills of reading, writing, speaking and listening to any/all areas of the curriculum in an effort to show the importance of literacy as a life skill and not just to pass English.

It is excellent practice for schools to have shared literacy marking strategies and to decide specific targets or literacy focus for students across the curriculum. In a small school, individual literacy targets can be shared with every teacher to inform lesson planning and marking. Moderating to ensure shared values and consistent marking across the curriculum via teacher inset sessions is a useful discussion point, not only to avoid disparity of student experiences of feedback but also to ensure teachers are identifying lessons where students excel in their writing and share effective techniques to support across the curriculum. Finally, involving students in the design and review of the literacy curriculum is a a good way to ensure relevance and autonomy.

Regardless of subject, these three aspects are essential to engaging young people in reading and writing opportunities:

- Purpose (Why is this important to read? Who am I writing it for? Do I care? Does anyone care about what I write?)

- Relevance (Does what I read matter to me? Why bother writing this? Will it make a difference? Is it related to my own interests / life? What can I express about myself through my words?)

- Community (How can I impact or help others by what I write? Can I support others to read or be mentored to read by someone in my community? Can my writing be part of creative enterprise, charity or fundraising?)

The moment a student feels motivated to read and write because they believe there is a purpose beyond getting better at reading and writing itself, literacy skills will begin to develop naturally and quickly. Writing doesn’t have to be essay format of course, lyrics, business plans, CVs, poems, stories, news reports, scientific analysis and film scripts, the list is endless and a vast range of writing opportunities should be woven into all subjects that encourage expression as much as focus on technical accuracy.

Vygotsky’s belief that learning should be a social act is key. Less teacher talk and more student discussion and discovery of their own answers will aid the type of informal language exploration that leads to building confidence in literacy.

Allowing thinking time, pair discussion time and so on leads to more fruitful responses and better articulated responses to questions in oral discussion. The family and community literacy of parents, carers, teachers and other school staff is of course also crucial, creating a nurturing culture of adults who also embrace and share their literacy experiences with the children they support.

More to come on the subject of literacy in future weeks as the federation of schools work with a range of international teachers to design literacy interventions that cross borders!

If you have time, please do share some of the ways in which you or your school supports literacy development. Is there a particular scheme of work that works well? How do you collaborate as a staff team to raise literacy levels? How do you collaborate with families, young people and the wider community in terms of literacy?

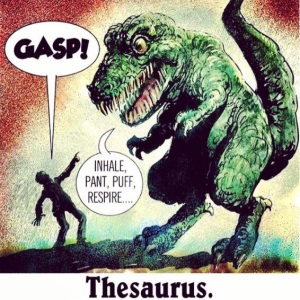

Just finished writing the post and saw this:

http://goo.gl/u4gLIy

What a great way to inspire creative literacy

LikeLike

Pingback: Our Federation Education Research Blog | Cornfield School

I agree that one moment or intervention can change the trajectory of children’s engagement with literacy. A refusal to give up on enthusiasm for literacy, even with the most vulnerable learners pays dividends

LikeLike

I strongly agree with every teacher being a teacher of literacy- not just reading and writing but deciding and digesting information in a broad range of ways so that literacy refers to emotional literacy, financial literacy, mental health literacy, social literacy and more. Preparing students to articulate their own thoughts and feelings and navigate their way through information is surely an important goal for teachers.

In my own lessons I bring reading to life, focusing on how something is read rather than the quantity of reading is the key to reducing fear of reading. We experiment with tone, pitch, pace and so on, adding physical actions to serve as punctuation to break the text up. Sometimes so that one person is captain of punctuation and does all the punctuation moves whilst narrator and other characters speak their lines.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great ideas. Practical subjects can be a fantastic way into literacy for children who do well in those subjects but feel overwhelmed by the structures of a classroom setting, or handwriting, spelling etc.

LikeLike